Super User

Access Versus Praccess

Last week there was some celebrations after Under pressure, Gilead expands Sovaldi licensing deal to four middle-income countries.

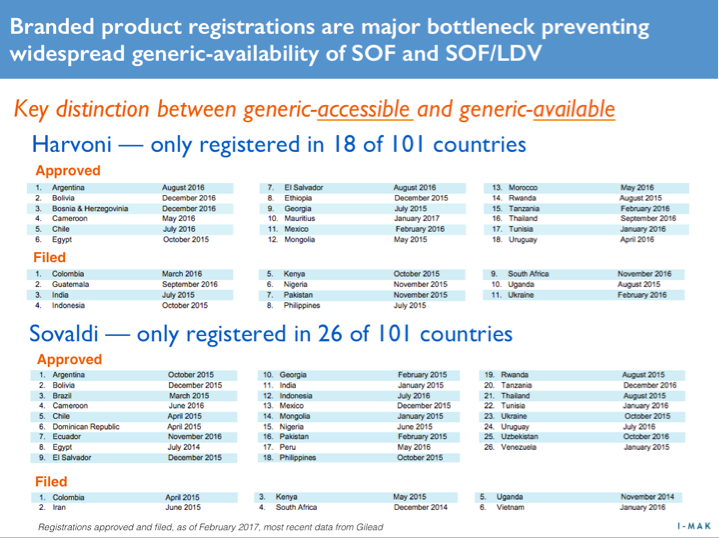

So great news, right? Not exactly, because in order for a country to have PRACTICAL ACCESS the product needs to be registered for sale there.

Now Sovaldi hit the market in late 2013 and back in February 2015 Gilead announced Gilead is committed to increasing access to its medicines for all people who can benefit from them, regardless of where they live or their ability to pay and providing a list of 91 countries where generics would be available. That list has since been expanded to include 101 countries.

That was 2 and a half years ago, so surely Sovaldi must be available in all the original 91 by now, afterall, Sovaldi was fast tracked by the FDA with one of the most rapid approvals ever seen...

Nope. To date Sovaldi is only registered in 26 of those 101 countries, with applications filed in another 6. That's 32/101 countries filed in 2 1/2 years.

- Without filing, there can be no registration.

- Without registration, there can be no availability.

- Without availability, there can be no patients treated.

This is the reality behind Gilead's PR-access. It is PR, it is not access.

AbbVie's New Hepatitis C Treatment Won't Cure Patient Access Issue

By Priti Krishtel

Last week, the FDA approved AbbVie’s Mavyret—a new hepatitis C virus (HCV) drug that treats all genotypes of the disease and cures more than 90% of patients within just 8 weeks of treatment. This has been reported as a threat to Gilead Sciences’ dominant position in the market, sparking rumors of a potential price war that could lower prices on the infamously expensive treatments.

There is reason to be tentatively optimistic. The initial published price on Mavryet was lower than expected at $13,200 per month—or $26,400 for a full course of treatment—appearing on the surface to be a significant discount from the $94,500 per-treatment course costs of Harvoni, Gilead’s market-leading treatment.

And while the published price is a step in the right direction to getting more people the treatment they need, it isn’t the whole story. The set Mavryet price is reflective of the current market conditions. With behind-the-scenes payer negotiations, the announced price on Mavyret is only an approximately 15% discount to the current net price paid for Gilead’s products.

While AbbVie’s pricing is now the lowest for a curative HCV drug, it is not a radical undercutting of Gilead prices. Millions of Americans with HCV—and tens of millions globally—are already blocked from getting treatment at the current exorbitant prices set by the pharmaceutical industry and the subsequent rationing of treatment approval by payers.

The United States is currently facing an HCV epidemic. There are an estimated 3.6 million Americans with HCV—and that number is expected to rise in the coming years. There is a cure, but every day 48 people in the United States die from HCV, the deadliest infectious disease in America. That’s because 2 out of every 3 Americans who have been diagnosed with HCV do not receive treatment, largely due to the high costs. States such as Louisiana and Pennsylvania are forced to ration treatment to the sickest of patients, and many insurers refuse to cover it because of the high price.

A week out from the FDA’s approval, it is not clear what the introduction of Mavyret will do to change this situation. What is clear, however, is that people should not die of an entirely treatable illness. One of the root causes of the unaffordability crisis is the fact that pharmaceutical companies such as Gilead over-patent drugs, including extending its market monopoly on Sovaldi for at least the next 2 decades.

Gilead’s initial price on Sovaldi has skewed what the market considered a fair price for HCV treatment. I doubt we would see this level of praise for AbbVie now if Gilead hadn’t launched this lifesaving medicine at $84,000 for a single course of treatment.

Until we address the core of the drug pricing problem—unjustified patents—pharmaceutical companies will be able to abuse the system to obtain monopolies on the market and charge astronomical prices that prevent people from getting access to disease-curing medicines.

About the Author

Priti Krishtel is co-founder and co-director of the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK), a US-based nonprofit group of scientists and lawyers working globally to get people lifesaving medicine. Prior to founding I-MAK, Krishtel obtained her law degree from New York University School of Law worked as a health attorney in the United States, Switzerland and India.

Breaking News: Study Shows HCV DAA Treatment Demonstrates 57% Survival Benefit

"To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to demonstrate the effect of newer DAA regimens upon survival. Treatment with 2 commonly used DAA regimens, PrOD and LDV/SOF, was associated with significant improvements in survival within the first 18 months of treatment, compared with demographically and clinically similar untreated HCV-infected controls. Treatment with either PrOD or LDV/SOF was associated with a 57% reduction in mortality, and attainment of SVR was associated with a 43% reduction in mortality….Benefits of treatment at a population level are expected to be substantial…..similar benefit can be expected with other DAA-based regimens"

Effect of Paritaprevir/Ritonavir/Ombitasvir/Dasabuvir and Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir Regimens on Survival Compared With Untreated Hepatitis C Virus–Infected Persons

Adeel Ajwad Butt Peng Yan Tracey G. Simon Abdul-Badi Abou-Samra

Clinical Infectious Diseases, cix364, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix364

Published: 20 July 2017

Abstract

Background

Interferon-based regimens are associated with a substantial survival benefit for persons infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). Survival data with direct-acting antiviral agents are not available. We conducted this study to quantify the effect of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir (PrOD) and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF) regimens upon mortality.

Methods

In the Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans (ERCHIVES), a well-established national cohort of HCV-infected Veterans, we identified HCV-infected persons initiated on PrOD or LDV/SOF, excluding those with human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, hepatocellular carcinoma, or missing HCV RNA or FIB-4 scores. For each case, we identified a propensity score–matched control never initiated on treatment. Primary outcome was survival. Outcomes were assessed using frequency of events, Kaplan-Meier curves, and Cox proportional hazards regression analyses.

Results

We identified 1473 persons on PrOD, 5497 on LDV/SOF, and 6970 propensity score–matched untreated persons. Treated persons were more likely to be obese and have cirrhosis, but less likely to have stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), alcohol or drug abuse or dependence diagnosis, and anemia. The proportion of persons who died was higher in the untreated group compared with either treatment group (PrOD, 0.3%; LDV/SOF, 1.4%; untreated controls, 2.5%; P < .001). A significantly larger percentage of treated patients survived to 18 months of follow-up, compared with untreated controls (P < .001). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, treatment with either regimen (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], .33–.57) and attainment of sustained virologic response (SVR) were associated with significantly lower mortality (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, .33–.99).

Conclusions

Treatment with PrOD or LDV/SOF and SVR are associated with a significant mortality benefit, apparent within the first 18 months of treatment.

Crisis, What Crisis? - Practivism

Here is a copy of the presentation, called "Practivism, it's the new black", given by Dr James Freeman at the International AIDS society meeting in Paris today.

Here is the text that went with the images.

Crisis, What Crisis?

This crisis. Look at this price comparison. I mean seriously?

We only have to look at Egypt to know these medications can be made affordably

Pricing negotiations are one sided and conducted by bandits

Our funders simply can not afford to cover the costs so…

We have rationing that sees only the sickest patients treated

And virtually nothing is being done for high burden populations like prisoners

And People Who Inject Drugs

Politicians pay lip service to the issue

Many advocacy groups are directly funded by Big Pharma*.

And in the Ukraine earlier this year generics were shot down by data exclusivity

Treatment rates are similar to infection rates

In short we are currently going nowhere fast.

Patients are stigmatized and don’t speak out so in the zeitgeist there is no crisis

But we desperately need a new balance between patent rights and patient lives

---

And now seven seconds of silence to remember those of us for whom treatment will come too late

One second for each patient who died during the time it's taken to give this presentation

Was it really only 50 years ago our Statesmen talked like this and the crowds came to listen?

---

What we call the “big picture” is really just the product of what each and every one of us chooses to do.

What we do as individuals, thinking globally but acting locally, exhibits a butterfly effect so I would like to suggest adopting this butterfly symbol and a simple slogan like "Wear if you care"

Direct Acting Antivirals and Liver Cancer Risk

Over the past year there has been quite a lot of discussion about the risk of liver cancer following treatment with Direct Acting Antivirals like Harvoni® and Sovaldi®.

Here is a quick explanation and the latest thinking from the academic gurus.

First, the risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC aka liver cancer) only starts to rise when patients develop cirrhosis, so for patients without cirrhosis there is little to worry about.

In patients with cirrhosis, and untreated Hepatitis C the annual risk of developing liver cancer is 3%. With SVR (cure) following treatment this risk falls to around 1%, so is much less.

In patients who have already had one HCC, treatment increases their short term risk of getting another one (this is probably one they already have but is simply too small to see) and demands very close monitoring both during and immediately after treatment.

So the bottom line is pretty simple. Treat before you get cirrhosis, but if you already have cirrhosis, you are still better off treating. If you have previously had an HCC you can still treat but need very close follow up.

Below you will find the text of a press release from EASL 2017. EASL is the European Association for Study of Liver Diseases and represents the best experts in the world telling it how they see it.

ILC 2017: Is direct-acting antiviral therapy for Hepatitis C associated with an increased risk of liver cancer? The debate continues

Eight studies being presented at The International Liver Congress™ 2017 demonstrate contrasting evidence on the potential link between direct-acting antiviral treatment for Hepatitis C and liver cancer

April 20, 2017, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: According to data from eight studies being presented at The International Liver Congress™ 2017 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, there remains continued debate on whether patients are at risk of developing liver cancer after achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) with a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen for Hepatitis C virus (HCV). Investigators will present the results of their studies that show both sides of the argument – DAA therapy is associated with a higher risk of liver cancer compared with interferon-based therapy, versus there is no difference in liver cancer risk following cure with either therapy.

Whilst remarkable progress has been made in the development of successful antiviral therapies for HCV infection, some recent studies suggest that curing patients does not eliminate the risk of developing liver cancer. There also appears to be an unexpectedly high rate of liver cancer (also known as hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC]) recurrence in patients who previously had their tumour treated successfully and had received DAAs.

This claim was further supported by a Spanish study led by Dr Maria Reig and Dr Mariño, Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Spain in which patients with HCV and HCC who had previously been cured of HCC received DAA therapy. After a median 12.4 month follow-up, following treatment with DAAs, the rate of HCC coming back (recurrence) was 31.2% (24/77) and of those who received HCC treatment at recurrence, 30% (6/20) of patients presented progression in the immediate 6-month follow-up. This is an update of the study that will be published in the May 2017 issue of Seminars in Liver Disease, and is available here: https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-0037-1601349.

“Our study offers further support to previous findings that there is an unexpected high recurrence rate of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with DAAs, and that this association may result in a more aggressive pattern of recurrence and faster tumour progression,” said Dr Maria Reig, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Group, Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Spain, and lead author of the study. “These data indicate that there needs to be further research conducted in this area, clarifying the mechanism for the association between liver cancer recurrence and DAA therapy.”

Identifying those patients at risk of liver cancer is essential, a task that Dr Etienne Audureau, Public Health, Henri Mondor University Hospital, Créteil, France, and colleagues attempted to achieve by developing a prognostic tool for HCC. They found that in patients with severe scarring of the liver due to HCV (compensated cirrhosis), failure to achieve SVR was the most influential factor in predicting liver cancer. In addition, risk factors for liver cancer differ according to SVR status. The investigators recommend that in patients with compensated cirrhosis, eradication of HCV should be achieved before liver function is impaired and people who have achieved SVR should be monitored for liver cancer after 50 years of age.

The mechanisms behind the development of liver cancer following HCV cure are not yet understood. One group of investigators led by Prof Thomas Baumert, Inserm Institute for Viral and Liver Diseases, University of Strasbourg, France, aimed to investigate if HCV infections produce epigenetic and transcriptional changes that persist after the infection is cured, and whether these epigenetic changes drive liver disease and HCC following cure. They found that the epigenetic and transcriptional changes are only partially reversed by DAAs and persist after HCV cure, suggesting that these changes are a driver for liver cancer that develops after HCV infection has been cured. The investigators concluded that these findings open a new perspective to develop novel biomarkers to identify patients at high risk of HCC and provide an opportunity to develop urgently needed strategies for HCC prevention.

On the other side of the debate, a systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regression study, by Prof Gregory Dore and Dr Reem Waziry from The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, and colleagues, found no evidence for higher risk of HCC occurrence or recurrence following DAA treatment, compared with interferon-based HCV therapy. A total of 41 studies, including 26 on HCC occurrence and 15 on HCC recurrence (in total, n=13,875 patients) were included. In studies assessing HCC occurrence, average follow up was shorter and average age was higher in DAA studies compared to interferon studies; incidence was lower with longer follow-up and younger age. In studies assessing HCC recurrence, average follow up was also shorter. Ultimately, in the meta-regression analysis, no evidence in favour of a differential HCC occurrence or recurrence was found between DAA and interferon regimens, after adjusting for study follow-up and age.

“Recent studies have reported contradicting evidence on risk of hepatocellular carcinoma following direct-acting antiviral therapy; our aim was to bring some clarity to this,” said Prof Gregory Dore, Kirby Institute and lead author of the study. “These data show the higher incidence of HCC observed following DAA therapy can be explained by the shorter duration of follow-up and older age of participants, rather than the DAA treatment regimen.”

A Scottish study, led by Dr Hamish Innes, School of Health and Life Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland, found that the risk of liver cancer following SVR was not associated with the use of DAAs, but baseline risk factors. Furthermore, risk of HCC development was similar in patients taking interferon-free regimens versus interferoncontaining regimens, following a multivariate adjustment (IRR: 0.96, p=0.929) and no significant differences in HCC risk were found when treatment regimen was defined in terms of DAA containing regimens versus DAA free regimens. These data indicate that rather than the treatment regimens themselves, it is the baseline risk factors that determine risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Another interesting study in Japanese patients with HCV genotype 1 infection, found a reduced incidence of liver cancer following achievement of SVR after 12 weeks of therapy with an interferon-free regimen (ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir) to a similar degree as that obtained with an interferon-containing regimen (simeprevir with peginterferon plus ribavirin). This study, which was conducted by Dr Masaaki Korenaga, Kohnodai Hospital, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Chiba, Japan, and colleagues, also found that unexpected development of liver cancer following SVR in patients without previous liver cancer could potentially be predicted by imaging procedures (computer tomography or enhanced magnetic resonance imaging).

Similarly, a Chinese study led by Dr George Lau, from the Beijing 302-Hong Kong Humanity and Health Hepatitis C Diagnosis and Treatment Centre, in Beijing, China, found no increase in the incidence of liver cancer in patients who achieved SVR12 with DAA compared to peginterferon plus ribavirin.

A Sicilian study conducted by Dr Vincenza Calvaruso, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy, and colleagues, demonstrated that patients who achieved SVR with DAAs had a similar risk of developing liver cancer when compared to historical controls of patients with compensated cirrhosis who achieved SVR after interferon-based therapy. In addition, those who achieved SVR with DAAs had a lower risk of developing liver cancer than those patients whose HCV infection was not cured.

“The original observations made by researchers from the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Group have sparked a huge number of studies aimed at verifying the potential association between DAA treatment and increased HCC recurrence after cure,” said Prof Francesco Negro, Divisions of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of Clinical Pathology, University Hospital of Geneva, and EASL Governing Board Member. “At this stage, there is no reason to alter treatment guidelines until the issue is definitively clarified. We cannot exclude, however, that we may have to revise post-SVR surveillance in some specific patient subgroups.”

- Ends -

About The International Liver Congress™

This annual congress is the biggest event in the EASL calendar, attracting scientific and medical experts from around the world to learn about the latest in liver research. Attending specialists present, share, debate and conclude on the latest science and research in hepatology, working to enhance the treatment and management of liver disease in clinical practice. This year, the congress is expected to attract approximately 10,000 delegates from all corners of the globe. The International Liver Congress™ 2017 will take place from April 19 – 23, at the RAI Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

EASL Response to the Cochrane Systematic Review on DAA-Based Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C

Here is the response from EASL to the recent Cochrane review. http://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/jhepat/CochraneEASLJMP003.pdf

EASL, the European Association for the Study of the Liver, one of the world leading associations of liver specialists, feels compelled to express its serious concerns after the recent publication of a Cochrane Group systematic review entitled “Direct acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C” by Jakobsen et al. After reviewing 138 clinical trials, including 25,232 participants, the authors conclude that: “Overall, direct acting antivirals (DAAs) on the market or under development do not seem to have any effects on risk of serious adverse events. […] we could neither confirm nor reject that DAAs had any clinical effects. DAAs seemed to reduce the risk of no sustained virological response. The clinical relevance of the effects of DAAs on no sustained virological response is questionable, as it is a non-validated surrogate outcome. All trials and outcome results were at high risk of bias, so our results presumably overestimate benefit and underestimate harm. The quality of the evidence was very low.”

The inability of the authors of the Cochrane review to determine a clinical benefit of DAA-based treatment of hepatitis C unfortunately reflects their flawed methodological approach and their ignorance of the natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and associated systemic diseases. The review examines the intervention in a clinical vacuum that fails to accept that DAA treatment to attain an SVR is a pivotal outcome of treatment, and does not accept the likelihood that an SVR will reduce the risks of long-term outcomes of hepatitis C.

With this deduction comes responsibility. The uncertainty created by the illconceived Cochrane group’s conclusions and the attendant press publicity could grievously affect policy making, and constrain the gathering momentum for diagnosis, testing and linkage to care of individuals with hepatitis C. It will create dangerous confusion in the mind of patients treated or about to be treated and their families. The World Health Organization (WHO) has published an authoritative Global Hepatitis Report, expressing its alarm at the burden of disease, and has promulgated critical targets for global elimination of hepatitis C by 2030. In the absence of a prophylactic vaccine, the Cochrane review jeopardises treatment as a necessary intervention to reduce the global morbidity, mortality and prevalence of chronic hepatitis C.

The primary endpoint in DAA investigational drug development trials has been the sustained virological response (SVR), i.e. undetectable HCV RNA 12 or 24 weeks after completion of treatment, which corroborates permanent elimination of the viral infection. The Cochrane review evaluated the effect of DAA treatments on several outcome measures, including hepatitis C-related mortality, all-cause mortality, serious adverse events, no SVR and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Most of their conclusions are flawed.

- The report from 32 trials including 7115 participants indicates that a total of 1180/1692 (69.7%) patients in the DAA groups and 915/5194 (17.6%) patients in the control group had “no SVR” during the observation period. This can only be an error as the authors deduce that meta-analysis showed that DAAs “seemed to reduce the risk of no SVR (risk ratio=0.44, p <0.00001) […]“.

- It is inappropriate to have pooled the data to include 57 trials that included drugs that have been withdrawn or discontinued. These are experimental drugs that have been discarded for lack of safety or inferior efficacy and that have been superseded by more effective and safer drugs, making the review dated and ignorant of current clinical decisions and guidelines in the context of a rapidly progressing field. Including treatments that are not or no longer used, and/or overly heterogeneous introduces a bias in the meta-analysis.

- From 43 trials involving 15,817 patients, the authors report serious adverse events (SAEs) in 2.7% of DAA-treated patients versus 5.5% in the control group during the observation period. They conclude that there is no firm evidence that DAAs reduce risk of SAEs. However, the terminology is clouded as the authors fail to clearly indicate whether they consider drug-related SAEs or clinical SAEs, i.e. clinical events resulting from the natural history of HCV infection which would happen months to years after the period of observation of the clinical trials.

- The HRQOL analysis has missed many recent studies. Several systematic reviews have been performed which have shown significant improvement in quality of life parameters with DAA therapy. The results show improvement over interferon and ribavirin-based treatments and are an encouraging aspect of an SVR with chronic hepatitis C, that further support the use of the SVR as surrogate. Very detailed and comprehensive analyses have been compiled before, during and after treatment objectively demonstrating improved patient-reported outcomes.

- The major weakness of the Cochrane review is that results are only assessed at “maximum follow-up”. These are of course short-term results for a disease with a long clinically latent period. A meta-analysis should only evaluate the primary endpoint selected by the clinical studies. The trials were not designed or powered to capture long-term outcomes such as hepatitis C-related morbidity or all-cause mortality, but to establish whether infection, reflected by persistent viremia, could be safely and effectively terminated.

The risk of clinical liver outcomes increases with aging and duration of disease. It is the result of chronic production of viral antigens during ongoing infection which incite host immune responses. The resulting hepatic inflammation in turn triggers fibrogenesis, the basis of liver disease progression towards aggravating fibrosis, cirrhosis and, ultimately, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The harmful effects of chronic hepatitis C take years to develop in patients that generally remain asymptomatic for long periods of time. Thus, although there is variation in rates of progression of fibrosis, early disease does not indemnify an individual from subsequent progressive disease, that can be accelerated by various cofactors and comorbidities. The authors of the Cochrane review have unfortunately not considered the possibility, the necessity and feasibility of arresting progression of early stage disease to more advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, or the ultimate development of HCC.

Achieving SVR, i.e. eliminating the infection, removes the trigger, thereby halting or considerably slowing the progression of liver disease. Terminating active infection also alters the natural history of a number of HCV-induced extrahepatic morbidities, such as diabetes and renal insufficiency. This has been clearly demonstrated by long-term follow-up studies in patients with chronic hepatitis C cured of their persistent infection during the interferon era. An SVR is associated with normalization of serum aminotransferases and improvement or disappearance of liver necroinflammation and fibrosis in patients without cirrhosis. Hepatic fibrosis generally regresses and the risk of complications such as hepatic failure and portal hypertension is reduced in patients with severe liver disease. Recent data showed that the risk of HCC and all-cause mortality is significantly reduced (although not eliminated to zero) in patients with cirrhosis who clear HCV compared to untreated patients and non-sustained virological responders. For the first time, DAAs have allowed patients with decompensated cirrhosis access to anti-HCV therapy, improving their liver function and reducing the indications for liver transplantation in a large proportion of cases, with a major impact on transplant programs already evident. Moreover, the possibility to treat patients after solid organ transplantation with high infection cure rates has opened the door to the use of HCVpositive grafts, increasing transplantation rates, reducing on-list mortality and containing healthcare costs for management of patients on the transplant waiting list.

National and international regulatory authorities have accepted the primary endpoint of an SVR and demonstrable safety as evidence for DAA licencing. Because the complications of chronic hepatitis C take years to occur, depending on the stage of liver disease, and clinical trials with new DAAs with SVR as main endpoint last only a few months, the benefits in terms of clinical outcomes of achieving an SVR cannot be measured in these trials. The Cochrane group’s conclusion is therefore illogical and inappropriate, as it fails to respect the methodology this organization has developed. The Cochrane review also ignores the opportunity of reducing the risk of transmission from viremic individuals, particularly in highrisk groups. Overall, the Cochrane review displays a lack of understanding of hepatitis C and drug development in the context of a transmissible infectious disease with a long natural history.

The Cochrane review authors’ conclusion that “randomised clinical trials assessing direct effects of DAA are needed” suggests an ethical anathema of leaving patients untreated to accrue increasing hepatic fibrosis, in the face of treatments that are likely to arrest viral replication in the overwhelming majority. This conclusion evokes memories of the infamous Tuskegee study conducted by the United States Public Health Service, in which patients with syphilis were left untreated to observe the natural history even after advent of and proven efficacy of penicillin. This unethical approach is unacceptable in a context where: (i) the HCV treatment landscape has markedly altered with the introduction of DAA-based regimens which in both clinical trials and real-world data have shown remarkable SVR (i.e. infection cure) rates in treatment-naïve and -experienced patients with or without cirrhosis across all genotypes; (ii) modelling has clearly demonstrated the benefits of DAA-based therapies in reducing long-term hepatitis C-related morbidity and mortality as compared to no treatment (individual benefit) and reducing HCV transmission (collective benefit). In summary, to arrive at such a flawed conclusion reflects the squandering of a vast amount of considerable time-consuming endeavour and significant public funding. The premise of the Cochrane review will be viewed as so egregiously mistaken that the conclusions will rightly be disregarded. As the findings do not assist or advance the field, they will not be pertinent to clinical decision making or guidelines.

EASL will continue to emphasize and reinforce the fight against HCV and to lend its support to the international efforts aimed at eliminating HCV, a major aetiology of severe liver and extra-hepatic diseases, complications and related mortality, by 2030. There is no precedent for a disease to be eliminated only 40 years after the discovery of its causal agent thus far. This chance cannot, and will not be missed.

The Lancet - What is the impact of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection?

This article was just published in the Lancet

The introduction of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medicines in 2013 revolutionised the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The efficacy of DAA therapy is impressive—in many clinical trials HCV cannot be detected by sensitive laboratory assays in more than 90% of people who complete DAA therapy, and observational studies have documented similar results.1, 2 High efficacy combined with low rates of adverse events have led WHO to include DAAs in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.3 Several countries, including Australia, Georgia, Iceland, and Morocco, have started national DAA-based treatment programmes to eliminate HCV infection, and WHO has called for the expansion of HCV therapy with DAAs as part of its global hepatitis elimination strategy.4

HCV is an important contributor to global mortality, causing an estimated 399 000 deaths each year worldwide, and as HCV treatment expands, it is anticipated that mortality from HCV infection will decline.5 However, because the annual risk of death from HCV infection is low and the DAAs were introduced only recently, there are limited data on how these drugs affect mortality. Clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy of DAAs do not assess mortality as an outcome but rather a surrogate outcome called the sustained virological response (SVR). An SVR is defined as the absence of detectable HCV by nucleic acid testing of blood samples obtained 12–24 weeks after completion of HCV therapy. An SVR is deemed equivalent to a cure because once an SVR is achieved, it is maintained in more than 99% of patients, even after years of follow-up.6 Also, an SVR is associated with resolution of cirrhosis in about half of patients with cirrhosis followed-up clinical trials.7

However, documenting in a clinical trial that DAAs result in an SVR is not the same thing as showing that they reduce mortality or morbidity. A recent systematic review by Jakobsen and colleagues8 from the Cochrane Hepatobiliary Group sought evidence from clinical trials of HCV therapies to assess this issue. The authors reviewed randomised clinical trials that used SVR as the primary outcome in people receiving DAA therapy compared with those either not treated or treated with other regimens (primarily interferon-based therapy). Jakobsen and colleagues concluded that DAAs were effective in producing an SVR (relative risk 0·44, 95% CI 0·37–0·52); however, the analysis did not find a reduction in morbidity or mortality after DAA therapy. At first sight, this conclusion seems to contradict systematic reviews of observational data that show that people who have an SVR after treatment with interferon and ribavirin had a 50% (95% CI 37–67) reduction in overall mortality and 76% (95% CI 69–82) reduction in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma as compared with people who were treated but did not achieve an SVR.9, 10 The reduction in overall mortality was even greater (81% [95% CI 72–87]) when persons with an SVR were compared with those not treated.9 Other studies have shown improvements in extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection and quality of life among people with an SVR after DAA treatment.11, 12 Data on the effect of DAA therapy are also beginning to be reported from national programmes that are scaling up HCV therapy. In England where HCV therapy increased by 48% in 2015, compared with 2014, there were reductions in the incidence of HCV-related cirrhosis (42%), liver transplantations (32%), and deaths (8%).13

Observational studies are biased towards showing an effect of treatment since treatment decisions are based on the likelihood of a successful outcome, and people achieving an SVR may be predisposed to a better outcome for reasons unrelated to the treatment. However, the magnitude and consistency of health benefits across studies and outcomes support the conclusion that HCV therapy resulting in an SVR substantially reduces mortality and morbidity.

How to explain these apparently contradictory results? An important difference between the studies reviewed by Jakobsen and colleagues is the duration of follow-up, which was short at an average of 34 weeks compared with an average of more than 5 years in the other reviews.9, 10 Simply put, the clinical trials included in the systematic review by Jakobsen and colleagues were not designed to answer the question posed by the authors about the effect of DAA treatment on morbidity or mortality. These studies generally followed up patients for only 24–48 weeks after the completion of DAA therapy, and the risk of HCV-related disease and death during such a short period is extremely low because the harmful effects of chronic HCV infection take years to develop. In fact, no morbidity was reported, and only 16 deaths occurred among the 2996 patients enrolled in all the DAA trials that were assessed by Jakobsen and colleagues. Thus, the statistical power to show a difference between the two groups is very low. In addition, the non-intervention groups in many of the studies included in Jakobsen and colleagues' systematic review did in fact receive HCV therapy, primarily an interferon-based regimen, which would minimise any mortality benefit of DAA therapy. Finally, Jakobsen and colleagues' study included early, less effective DAA regimens that were discontinued or withdrawn before marketing. They propose that, to resolve definitively whether DAA therapy reduces morbidity and mortality, randomised clinical trials with a non-treatment comparator group be done with clinically relevant outcomes such as death. Clearly, with the ready availability of safe and effective DAAs and ample evidence showing the health benefits of achieving SVR, such a study design is unethical and would be unacceptable to institutional review boards and harmful to patients' health. Several organisations, such as patients' groups and international hepatology associations, have expressed their concerns about the methods and conclusions of the Jakobsen review.14, 15, 16

People who are knowledgeable in the field of HCV therapy can readily ascertain the limitations of the approach taken in the systematic review by Jakobsen and colleagues and will be able to place their results in the proper context relative to other data that document the health benefits of DAA therapy. But for some patients, health-care providers, and decision makers who may be less knowledgeable about HCV therapy, this type of analysis, especially as reported in the mainstream media,17 could lead to conclusions that DAA therapy has no benefit, resulting in decisions to decline to prescribe or take DAA therapy or to decline to approve budgets for DAA treatment programmes, particularly in view of their expense. This would be a tragic outcome, as it would lead to preventable deaths. Public-health policy makers who must decide on budget allocations for HCV treatment cannot wait for perfect data on mortality endpoints, since the types of trials that would generate these data will never be done. Rather, they must assess available, albeit imperfect, data from observational studies and trials using surrogate outcomes that are reliably predictive of clinically important outcomes. Based on the fact that DAA therapy is safe and effective in achieving SVRs, that the SVRs are durable in most patients, that HCV-induced liver damage improves after SVR, and that observational data show a large reduction in morbidity and mortality, health-care decision makers and providers can take comfort that the evidence is strong in favour of treatment. A more definitive assessment of impact on morbidity and mortality will take time, but this should not be used as a reason for denying HCV therapy and delaying efforts to eliminate HCV infection.

How do I fix my insomnia

About 1 in 5 patients taking Direct Acting Antivirals will get insomnia. Here is a post of mine from some years ago about how to manage it.

Insomnia is a common and often frustrating problem. Part of the reason it's frustrating is that, unless an accurate diagnosis of the root cause(s) is made, treatments tend to be temporary band aid solutions and rapidly lose their effectiveness.

Do you have an underlying medical problem?

There are a range of medical condition that can cause insomnia.

Chronic pain, sleep apnoea or a need to urinate frequently caused by an enlarged prostate gland can all cause insomnia.

Diseases like arthritis, cancer, heart failure, lung disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), overactive thyroid, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease have all been implicated.

Mental health problems like stress, anxiety and depression can also cause problems.

Many of these issues are amenable to treatment, and by fixing the root cause, sleep patterns can return to normal.

Are your medications to blame?

- Alpha-blockers

- Beta-blockers

- Steroids

- SSRI antidepressants

- ACE inhibitors

- ARBs

- Cholinesterase inhibitors

- H1 antagonists

- Glucosamine/chondroitin

- Statins

Note that you should consult with your doctor before stopping any prescribed medications.

Are your daily habits contributing?

There are many habits and work patterns that promote poor sleep

- Not enough light at midday and too much light (device screens) at night

- Shift work - this scrambles your body clock (circadian rhythm)

- Eating late in the evening

- Fluids in the evening (we were all trained as children to wake up and not wet the bed)

- Excess caffeine, nicotine and other stimulant (ie Red Bull) consumption

- Using stimulants in the afternoon and evening

- Not getting enough exercise

- Too much alcohol - although alcohol is a sedative it prevents entry into deep sleep

Could your sleep hygiene be improved?

If you use your bedroom for other activities than sleep and sex you are missing the opportunity to program your thinking along the lines of go to bed, go to sleep.

You will sleep better if:

- You have got a good dose of daylight during the day, and less light at night

- Your bedroom is pitch black

- Your bedroom is quiet

- You bedroom is not too hot, not too cold

- You have a comfortable mattress

- You have a comfortable pillow - not too high or too low, too soft or too firm - get one that's just right (and remember they wear out over time)

- You have enough blankets so you're not too hot when you go to bed, but also don't wake up freezing when it cools off in the early morning

What can my doctor do for me?

For a start, any doctor worth his/her salt can discuss everything with you and look for root causes. It's always best to fix the source(s) of problems.

A simple plan (from Dr Margaret Hardy)

- Work out average amount of actual sleep per night from sleep diary

- Choose a regular wake-up time

- Set a regular bedtime by subtracting average sleeping hours from the planned wake-up time

- Review at weekly intervals and, if tired, increase time in bed by going to bed 30 minutes earlier

Your doctor can also provide medications including:

- Melatonin (which re-sysncs your body clock and is thus really good for shift work and jetlag

- First generation sedating antihistamines (promethazine, doxylamine)

- Benzodiazepines (temazepam, zopiclone, zolpidem and many others) which are good for short term (particularly stress related insomnia). Long term you become first tolerant (needing ever increasing doses) and then addicted (needed the medication or you won't be able to sleep)

- Antidepressants like amitriptyline and mirtazipine which are used (usually in low doses) not to treat depression but for their common sedating side effect. Their advantage over benzodiazepines is that tolerance is far less of an issue, so they can be used longer term.Don't despair. Most people can get

Don't despair. Most people can get a far better nights sleep with a few simple changes.

Talk to your doctor, or see one of our expert GPs online from the convenience of home.

Dr James Freeman

Bad Science

Yesterday the Guardian published an article called 'Miracle' hepatitis C drugs costing £30k per patient 'may have no clinical effect'

The problem with this sensationalist headline is that while it is reporting what was said by the Cochrane Collaboration what they looked at was trial specifically designed to test SVR rates, and not specifically designed to look at long-term outcomes.

Here is a commentary from Dr Andrew Hill and the study to which he refers which was presented at AASLD in 2015 and published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Reversal Of Liver Fibrosis - Then and Now

There is some really interesting stuff happening in the "reverse liver fibrosis" realm.

Here is state of the art in 2009 (great review of the mechanism) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702953/ where we had no clear candidates, and

Here is state of the art in 2015 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4703795/ where we have literally hundreds of candidates (coffee and milk thistle (silymarin) and resveratrol are in there), and

Here is the state of the art in 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4754444/ in an article called Promising Therapy Candidates for Liver Fibrosis

I like this bit from the conclusion:

Since both animal experiments and clinical studies have revealed that liver fibrosis, even early cirrhosis, is reversible, treating patients by combined therapies on underline etiology and fibrosis simultaneously might expedite the regression of liver fibrosis and promote liver regeneration.